with Stephen Johnson • Thu 2 October, 2025

Hey Big Thinkers,

Stripping context from familiar things makes them uncanny. The webcomic Garfield Minus Garfield has no clever tabby cat — just a sad Jon Arbuckle talking to himself. Seinfeld without the laugh track makes Jerry and the gang sound insane. And an empty, dimly lit hotel hallway — no doors ajar, no housekeepers, no voices through the walls — can feel less like a real place and more like a dream half-remembered.

That last one belongs to the “liminal space” aesthetic, which became popular online around 2019. The name refers to those in-between places we’re not meant to linger in — stairwells, airports, hallways — spaces that make sense only in relation to what comes before or after them. Stripped of context, these places can feel eerily dreamlike, familiar yet somehow wrong.

Liminal spaces aren’t just an internet phenomenon. The term comes from anthropology, describing the “ambiguous period when we leave an old identity behind but haven’t yet stepped into a new one,” writes neuroscientist Anne-Laure Le Cunff.

This week, she shows why life’s in-between spaces — the unsettling thresholds — are also where growth happens.

Read on,

Stephen

THE BIG IN-BETWEEN

Why liminal spaces are your brain’s secret laboratory

It’s no wonder life’s in-between stages feel so disorienting. Your brain is wired to crave certainty, so when you leave one role, relationship, or identity without yet stepping into the next, it sounds your internal alarm. But neuroscientist Anne-Laure Le Cunff argues this discomfort isn’t a flaw — it’s a feature. Liminal spaces, she writes, can act like a cognitive laboratory, heightening learning, creativity, and resilience by disrupting routine patterns. The key is learning how to flip that stress response into curiosity.

Fast Stats

4,000 — The approximate number of NASA staffers set to have left the agency by January 2026.

5 — The great thinkers who abandoned their own ideas, as highlighted by philosopher Shai Tubali.

3 — The telltale signs your boss is high on “toxic positivity.”

1803 — The year the ancient idea of the atom was redefined into our modern understanding of matter’s basic building block.

THE BIG TOPIC

David Kipping on how the search for alien life is gaining credibility

“NASA used to effectively ban the word ‘SETI’ in proposals,” says astronomer David Kipping. “Now there are grants funding it.” In his interview with astronomer and 13.8 columnist Adam Frank, Kipping explains the recently shifting tides in the search for alien life, the Fermi paradox, and why an “extragalactic SETI” might someday provide unambiguous evidence for the existence of life across the cosmos.

MINI PHILOSOPHY

Would you rather be an absurdist or an existentialist? Here’s the difference between the two.

By Jonny Thomson

I am drawn to people I almost certainly wouldn’t get on with. I sometimes look at old photos of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus in their post-war France black-and-white chic and think, “Oh, to share a Kronenbourg with them.” How cool would it be to stay up late, dancing, talking politics, and debating the meaning of life?

But then, I have a crash-to-earth moment. I go to bed at 10 p.m. and get up with the sun. I generally hate talking politics and have two left feet on the dance floor. I don’t even like Kronenbourg. Worst of all, I think I would find the constant dissatisfaction of it all a bit dreary. Because both the absurdism of Camus and the existentialism of Sartre and de Beauvoir are heavily hued with a shadowy ennui.

To know what the hell that even means, read this week’s explainer into two of the most popular philosophies today.

Subscribe to Mini Philosophy on Substack for even more from Jonny Thomson.

Popular Columns

Business: Are you an effective trailblazer?

Starts With A Bang: The 5 biggest mysteries about the origin of our Universe

Books: For the pharaohs, ruling Ancient Egypt meant mastering the Nile

Freethink: The End of Death as We Know It?

THE BIG IDEATION

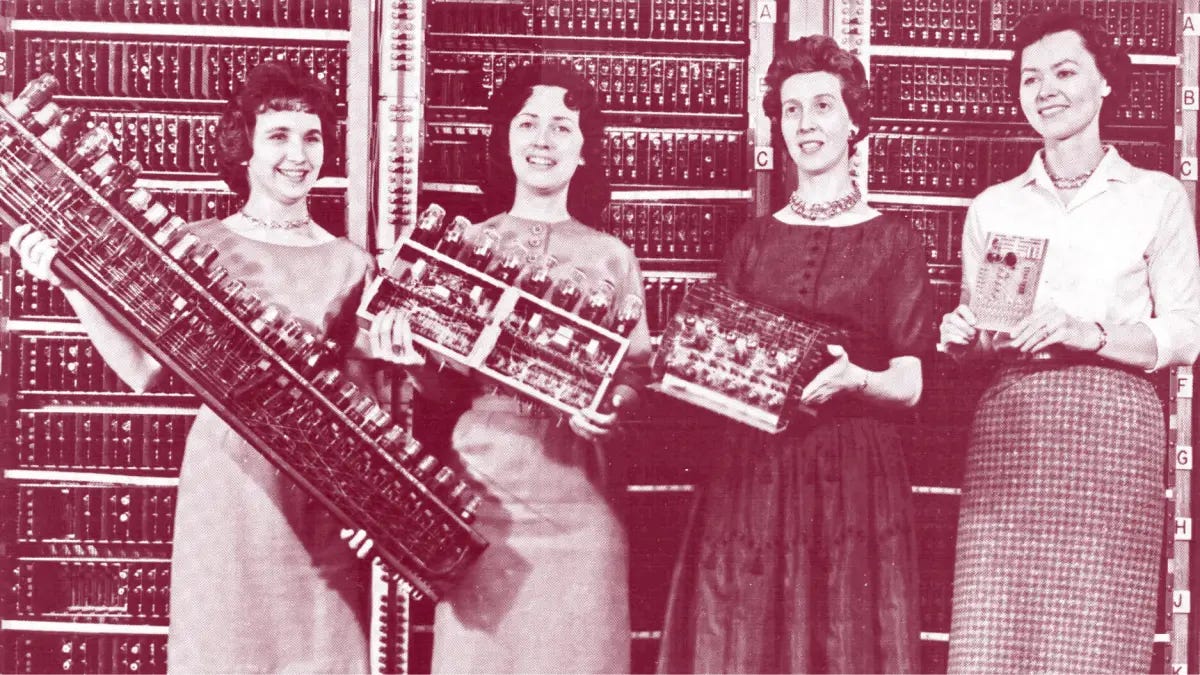

Why your AI strategy needs guidance from an 82-year-old computer

In 1943, the U.S. Army built ENIAC, the world’s first electronic general-purpose computer. Weighing 30 tons and packing in 17,468 vacuum tubes, it could perform thousands of calculations per second. The military hoped that computers would someday be able to predict outcomes — of markets, wars, elections — by reducing the future to math. Those dreams were soon crushed, in part by fighter pilots, who, to the military’s surprise, fought well not because they followed textbook flying rules like a program, but because they creatively deviated from the rules when it gave them an edge. That paradox — machines that can out-calculate us but not out-create us — still defines AI today, argues professor Angus Fletcher.

Stephen Johnson is the managing editor at Big Think.

Get more from Big Think:

Mini Philosophy | Starts With A Bang | Big Think Books | Big Think Business

The human brain is worth fighting for afterall.

Liminal spaces aren’t dead zones...