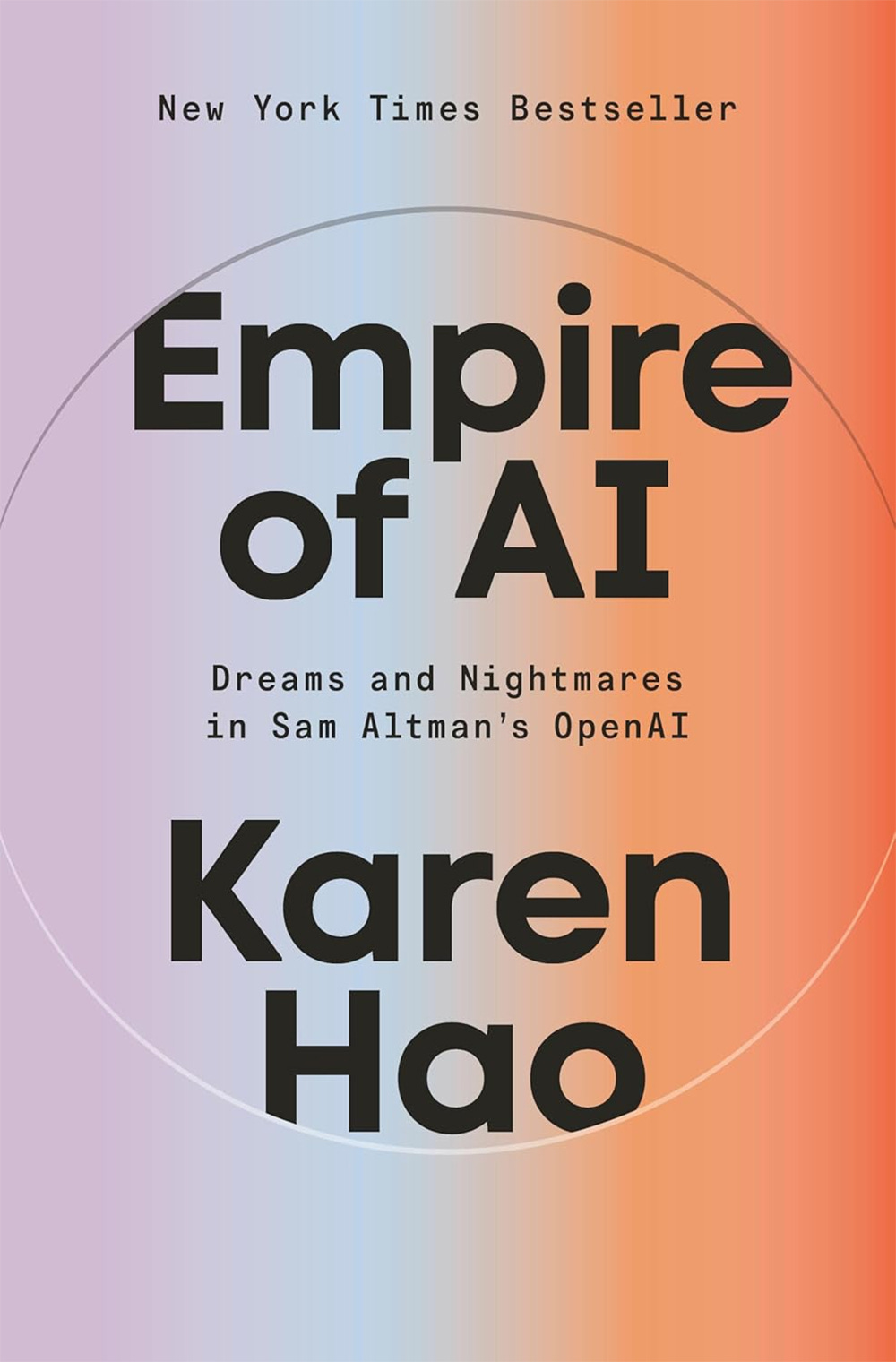

The boomer-doomer divide within OpenAI, explained by Karen Hao

There are two sides to the AI debate, and both are perpetuating the idea that AI is “inevitable, all-powerful, and deserves to be controlled by a tiny group of people,” says the Empire of AI author.

By Tim Brinkhof

In the introductory chapter of her book Empire of AI, author Karen Hao explains how Sam Altman’s temporary ouster from OpenAI in November 2023 was the result of an ideological rift that tore the organization’s leadership in half. No one contested OpenAI’s founding goal — to ensure artificial general intelligence (AGI), once developed, would benefit rather than destroy or enslave humanity — but there had been growing disagreement on the best way to reach it.

One side, united under Altman, argued that the funds required to create AGI could only be secured if OpenAI transformed from a nonprofit into a for-profit entity, while the other believed the introduction of private capital into the organization would get in the way of AGI serving its intended purpose. Altman’s side won, and the rest is history.

Hao was in the middle of an interview when news of the ultimately unsuccessful coup first emerged — not that the event significantly changed her view on the company or its role in the world.

When Musk and Altman co-founded OpenAI, they already had an egotistical motive.

Karen Hao

As the veteran Silicon Valley reporter and best-selling author tells Big Think in the interview below, OpenAI was born out of not only concern for the future of civilization, but also the desire to beat — and ultimately dominate — its competitors. In retrospect, its altruistic mission statement has helped both justify and enable the company’s unchecked growth. Even if reflective of a genuine fear about how AGI might be used, its function has been that of a marketing ploy, a story told to animate employees, attract investors, and silence alarmed members of the general public.

As suggested by its title, Empire of AI — released in May 2025 and based on interviews with more than 260 people employed by or close to the company — makes the case that OpenAI has developed into something analogous to a colonial empire, extracting resources and exploiting labor under the guise of innovating, civilizing, and elevating humanity to a superior state of being. But all empires crumble sooner or later — and often the fall is a direct result of internal efforts to stave off the inevitable.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Big Think: Reading your book, one can’t help but notice that OpenAI’s corporate culture seems kind of cultish. Is this an industry thing or specific to OpenAI?

Karen Hao: A lot of Silicon Valley companies cultivate a mission-driven ethos that gets people to buy into a certain ideology and venture, but OpenAI definitely took it to a different level. Sam Altman often tells employees that OpenAI is an unusual company. I think he means many things by that, but one of them is the degree of alignment he seeks to cultivate within the organization by way of its quasi-religious sense of purpose.

One aspect of empire-building is creating the banner of a civilizing mission under which to engage in a lot of bad stuff around the world. Just like the empires of old, OpenAI’s ability to put blinkers on its employees — to convince them that everything we do is ultimately worth it because the ends justify the means — is a key part of how the company managed to cultivate so much power and influence.

Big Think: The story of OpenAI — and the AI industry as a whole — unfolds rapidly. What are your thoughts on some of the major developments that have taken place since your book’s publication earlier this year?

Hao: One of the biggest changes that’s taken place since the book was [written] was Donald Trump’s reinauguration. The president has really codified a stance within the U.S. government that they are uninterested in holding Silicon Valley accountable. The fact that they’re instead abetting its expansion has, I think, only made the empire metaphor more relevant as there’s now a clear analogy to the British East India Company and the British Crown, where the Crown supercharged the company’s recklessness, nationalized it, and turned India into a colony of the U.K.

I can see this parallel playing out in real time, where the U.S. government sees the supercharging of OpenAI’s activities — and the rest of the AI industry’s activities — as a way to accumulate power in the world. And if one day they need to do whatever the equivalent of nationalizing this company is, my guess is that this administration is operating under the assumption that these companies’ assets around the world will eventually become American assets and belong to the American empire.

Big Think: OpenAI had quite a few comments on an article you wrote about the company and its history for MIT Technology Review in 2020. What has its response to Empire of AI been like?

Hao: Actually, OpenAI has not responded at all. Right before publication, Sam Altman subtweeted the book by saying there were some books coming out about him and that people should read the two he had participated in. Since there are only three in total, he was basically telling people not to read mine. But when he did that, it ended up generating a lot of attention for my book.

Now, their strategy seems to be papering over the book with a steady drum of press releases and trying to drip out positive news to cover it up.

Big Think: A recurring theme in your book is that OpenAI’s success stems in large part from its ability to create a narrative of success — imminent, unavoidable, tremendous. As the zeitgeist continues to shift from techno-optimism to pessimism and cynicism, how will the company keep that narrative intact?

Hao: Altman and other OpenAI executives often say that criticism is expected whenever you’re trying to do ambitious things. Because you’re breaking norms, because you’re the first mover, there will be backlash. There’s been a turn inward, with the company building more and more of a fortress that insulates it from external feedback. There were already religious undertones in many of the things they did, but with the building of the fortress, that has only intensified — especially after GPT-5, when public skepticism increased about whether their work was producing true advancements in AI capabilities.

You would think that might shake some AI developers about whether they’re on the right path, yet they’ve only doubled down. Rather than sowing doubt, it has made them more impervious to critiques of their approach. OpenAI was originally meant to have a very open orientation. Then it closed itself off, and now it’s continuing to close itself off more and more.

Big Think: After all the research you’ve done, do you think that OpenAI started off from a well-intentioned place but took a dark turn later down the road? Or were hints of what it would eventually become present at the very beginning?

Hao: I originally thought it was the former, but now I think it’s the latter. When Musk and Altman co-founded OpenAI, they already had an egotistical motive: They weren’t happy that Google was dominating AI development and wanted to be the ones who dominated it instead. And they came up with a really good story about why this was the morally right thing to do, why they were the good guys going on this purpose-driven quest.

It’s sort of logical that they shed the nonprofit aspect very quickly as it became a hindrance to the original goal: to dominate.

Big Think: You write that when GPT-2 came out, OpenAI itself warned of its dangers and potential misuses — warnings that many outside experts brushed off as a publicity stunt. How does this attitude relate to the company’s current strategies?

Hao: It took me a long time to really understand what happened with GPT-2. I eventually realized I was seeing the first clash between the boomers and the doomers within the company. The reason OpenAI initially decided not to release GPT-2 was because the doomers were leading the effort. Their stance was that they should advance things quickly but not release anything, so they could buy themselves time to figure out how to make their model “safer,” meaning making sure it doesn’t kill everyone.

After a bunch of backlash, I think both sides started changing their minds a little, partly because an open-source GPT-2 emerged that made it clear nothing civilization-ending was going to happen if it was released. But I think the boomers also felt really upset that they were getting dinged for a technology they didn’t believe should be withheld the way that the doomers did.

Big Think: Discussions about AI often fall into this doomer-boomer dichotomy, with doomers thinking AI will destroy the world and boomers thinking it will save it and make everyone rich and happy. Could it be that this dichotomy is itself a product of and a contributing factor to the growth of the AI bubble?

Hao: Yes, 100%. Boomer and doomer narratives perpetuate the idea that AI is inevitable, all-powerful, and deserves to be controlled by a tiny group of people. It enables Silicon Valley to continue its very anti-democratic approach to AI development, making decisions that affect billions of people with absolutely zero accountability.

Originally, I thought the boomer-doomer narrative was simply rhetoric — stories drip-fed to fuel their consolidation of power. But I realized while reporting that there are people who genuinely fall into the boomer or doomer camp. They genuinely believe AI could bring utopia or the demise of humanity. I spoke with people whose voices were trembling with anxiety, talking about AI becoming too powerful, going rogue in a couple of years, and killing all their loved ones and them as well. I sometimes compare it to Dune. It’s like someone originally created myths about what AI could be, but over time, even the mythmakers themselves turned into fervent believers.

Big Think: At risk of pathologizing people, where does this belief come from? Is it a result of Silicon Valley’s high-pressure work environment, where jobs are competitive, well-compensated, and quickly acquire an all-consuming importance?

Hao: There are people at OpenAI I have followed for years, and their beliefs have dramatically shifted since they first joined. They exist in echo chambers where everyone they know and speak to on a daily basis is talking in religious undertones and with fervent belief in what they’re doing. You can’t help but fall into that line of thinking yourself, especially because many of these people are highly intelligent, talented individuals. All of these highly capable, highly respected individuals are saying these things — of course you’re going to get sucked into the mythology.

I’ve been blown away by how deeply people engage with these issues … and how motivated they are to resist empires and build something better.

Karen Hao

Big Think: Circling back to doomers and boomers, what do you make of a book like If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies? Do you think its tone and content adds to the conversation in a productive way?

Hao: I don’t think it’s productive at all — it’s squarely doomer rhetoric. Eliezer Yudkowsky, the main co-author, is one of the most prominent people pushing this ideology right now, and it’s not based on any scientific evidence. He’s not talking in grounded reality, yet the book has sucked so much oxygen out of the room. It’s getting a ton of coverage — very prominent people are platforming both the book and the authors — and it continues to confuse public discourse by not focusing on the real problems: AI’s enormous environmental and public health costs, how it’s contributing to the affordability crisis, or [how it’s] destabilizing the economy. Instead, we’re sitting through yet another media cycle of, “Is AI going to kill us?”

Big Think: In that case, do you see such discourse playing into OpenAI’s favor?

Hao: Yes, and this gets at a huge part of my critique of the doomer community. Over the course of last year, they’ve tried to adopt this orientation of “we need to start building bridges” with other communities that are concerned about what’s happening with AI, and so they’ve been trying to move beyond existential-risk narratives to start acknowledging things like environmental concerns.

Whenever I engage with people in that community, here’s what I tell them: I appreciate that you’re starting to look at these other issues, yet you are still — by continuing to fixate on the existential-risk narrative — actively undermining the advancement of these other issues. You’re feeding into OpenAI’s power and the power of all these other companies, giving them justification for maintaining really tight control over the technology.

Some people in the doomer community will acknowledge all this. Some will even go as far as to agree that their own historical track record has been one of failure. They sought to slow down the technology’s development and somehow managed to do exactly the opposite. Worse, they fed into the recklessness and anti-democratic nature of this development.

Big Think: You note that the rise of OpenAI is rapidly closing off other, potentially more hopeful avenues in AI development. As resistance against the company increases, have you become more hopeful that some of these avenues will remain accessible?

Hao: I’ve actually become way more optimistic about this since the book came out, and there are two reasons for that. One is that, while on tour, I’ve been blown away by how deeply people engage with these issues, how nuanced their understanding is, and how motivated they are to resist empires and build something better.

A lot of people ask, “Should we have regulation and legislation?” I say, yes, we should — but we’re not in a political moment where that’s likely to happen. Still, dozens of communities are protesting against data-center projects, effectively blocking or reshaping them, and even implementing bans in some areas. People are [filing] lawsuits: artists and writers over IP, families over mental-health harms linked to AI. Civil society coalitions are challenging the way OpenAI converted to a for-profit model to better resource its nonprofit side. These movements are gaining momentum, connecting, sharing tactics, and organizing across borders. That’s part of how we can slow or disrupt OpenAI’s path.

The other reason I’m hopeful is that AI itself — and Altman’s increasingly extreme rhetoric — has started to backfire. The company keeps creating public kerfuffles: Altman announcing ChatGPT might move into pornographic content, the CFO suggesting OpenAI might seek a bailout for infrastructure debt, and ambitious plans for 250 gigawatts of data-center capacity costing $10 trillion by 2033. The escalation is so extreme that it’s making people deeply uncomfortable. Bubble rhetoric is growing, and more people are questioning whether this is the one and only way forward.

Building the most advanced plagiarism machines in existence should not be celebrated or rewarded.

What resonated for me here is the idea that both boomer and doomer narratives preserve inevitability. Once something is framed as unstoppable — whether utopian or catastrophic — it becomes easier to justify speed, concentration, and exemption from feedback.

The more interesting work feels like slowing the story down enough to examine what’s already being encoded.